Artist Bryan Chadwick

Congratulations to Bryan Chadwick for earning his place as the 2nd Place Winner in the 6th Edition!

Who are you?

I’ve been asking that question my entire life! My art is an effort to find out. It’s been said that all art is auto-biographical, even if it’s entirely abstract, so creating the art you are driven to make is a great way to plumb the depths of your existence, to ask yourself, “Why? Why me?”

Of course, I have biographical details like everyone else: born in Montreal, into a large English-speaking family, did all my schooling in French, summered on a lake in the woods with no electricity, no phones, no car, no TV… but there’s something else I’ve been after, something you can’t describe with words alone, hence...my art life.

Like many artists, as far back as I can remember, I’ve worried that the creative ‘nudges’ I’d get must be coming from a source outside myself. I couldn’t explain them, and that totally freaked me out. Later, I began to wonder if the ‘nudges’ were actually coming from within, perhaps from a recessive gene that has been passed on and programmed to go off in a particular individual at a particular time.

I viscerally recall the day I believe I became an artist. It’s pretty much my oldest memory.

Every night, after my mother tucked me into bed, on the third floor of a house my father designed on Mont-Royal, this beautiful white light would come swishing in through the windows. A momentary, exquisite flash of radiant light would ignite my entire room, casting shadows like X’s from the window frame all around me. Then I’d be left in utter darkness. Darkness is all the more extreme because of the sudden absence of light. But I knew the light would come back. And I knew exactly when it would come back.

One winter night, I was inspired to sneak out of bed, push a chair up against the radiator beneath my window, and clamber up to see where that light was coming from. Standing on the iron radiator grill, I saw out the window an incredible city stretched out before me, sparking in the snow, and the light was coming from the top of a tall building in the center of it. The light itself had four arms, and turned around and around, like an X, or a cross, from the top of the building which itself was shaped like a cross.

I heard the radiator begin to spurt and sputter, clanking, and it began to heat up. But I kept standing there. I was utterly mesmerized. Now I understood how I could tell when the light would return; it was a combination of geometry, symmetry, timing, and distance, as each of the four rays turned around the city, shining into my window momentarily as they passed. I had a sensation that I was learning something. I had to begin walking in place, lifting my feet one after another, because the radiator was really getting hot. But I couldn’t pull myself away. I kept watching the light. Regardless of the pain, I just freaking stood there. Ultimately, somehow, I let my baby feet get burned to the point of horrendous bubbling blisters that blew up to oozed watery goo in the days that followed.

I had to hide these wounds from my mother! If she found out that I’d been out of bed, I would be in big trouble. So I filled a pair of socks with handfuls of Nivea Cream and wore those goopy Nivea Cream socks until I eventually healed.

For those that don’t know Montreal, the building from which the famous rotating light comes is one that my father —an architect—was invited to submit designs for, but it was ultimately scooped up by the brilliant I.M Pei, who nailed it (pun intended) with a design it in the shape of a cross, or an X with a matching, rotating light on top. It’s called Place Ville Marie (Place of the Village of Mary.)

Seeking the source of the light (meaning, whatever is nudging me along creatively) finding out, then hiding it is what has defined my art ever since. I’ve been hiding my art for most of my life, as you know, and I’m only now beginning to share it.

Another incident was seminal in my becoming an artist.

I must have been about five when I was given my first-ever watercolor set. I was transfixed by those little, round tablets of color. Most of all, I was struck by how the wet colors spilled out of their dishes to swirl around and merge with other neighboring colors, creating fantastical art smudges on the white tray without any help from me.

I must have been taken to church around the same time and seen worshipers receiving the Eucharist because I came to assume that my paint tablets must be just like those little, circular, sacred wafers people were eating at the alter. "Hosts" they were called. Mum explained how people thought God was inside them. (We were not a religious family.) My paint tablets must have God inside them, too, I decided. That's how they can create art on their own with me just a bystander, I figured.

So... at home...trying to emulate what I'd seen at church, I chiseled the nice, deep red one out of the tray. Yes, it was thin and circular, just like those thingies. So I put it on the edge of my tongue, just like the worshippers had done, and snarfed it.

OMG—nasty! After sucking on the bitter red and crunching a few chalky bites, I spit the whole thing out, creating a small, bubbly abstract color field surrounding a broken wet disc of radiant red on my bright white pillowcase. Wow!— I loved the experience.

But again, I worried I’d get in trouble if my Mum found out I’d eaten the paint round. So I had to hide the evidence. It took forever to wash the red from my mouth and face, and I threw the stained pillow case, along with my now stained toothbrush, in the attic which could only be accessed by a trap door in my closet.

I think these were my first, formative artistic experiences. And already you can see a pattern: I’m not really in charge of them, I just innocently act them out. I’m nudged to pursue something very specific, I embody it or experience it physically, then... I hide it. My art has always been about kind of keeping a record of these experiences, ‘documenting’ them, codifying them, and understanding how they fit together so that if ever a day came when I was nudged to share them properly, I’d have a beautiful, verifiable, time-stamped way of expressing them.

I have a series of paintings called, “HOSTS” that recall the paint-eating adventure, each work features a single color round and the color melting out around it. Here’s “The Blue Host”:

What inspired you to begin utilizing sculpture as a medium?

“What inspired you”, again, is the the crux of my artistic struggle and I’m still sorting through it! I do recall the first ‘sculptural’ thing I ever made. It was in Mrs. Pets’ 7th grade art class. We were experimenting with papier mâché. I was nudged to make something highly specific: a seed-like form, painted red on the outside, like an apple but more like a pomegranate seed, and inside was to be a long stairway leading to a special city with lots of tall, silver skyscrapers. I was inspired to call it, “The Apple Island”, and it stood in our school’s foyer display cabinet next to popsicle stick houses and painted rock paper weights for the rest of the year as an object of curiosity. I recall parents asking, “Whose kid made… uh? OMG! What the heck is this?”

Did I make it because I was able to foresee (or tell myself) that I was to one day go to live in “The Big Apple” as I do today? As I said, I’m on the fence about all this.

Can you discuss the inspiration and thought process behind “The Starry Night Geode”?

Yes, in each of my GEODES, I’m inspired to recount experiences (similar to the ones above) that have nudged me forward. The Starry Night Geode is my way of saying that certainly other artists’ work has inspired me, i.e; it’s not all inexplicable, kooky-nutty woo-woo experiences. I think all artists are a product of the artists that came before them. Art is evidence of an evolutionary process. It tracks human development. Looking at art history is like watching Darwinism unfold in front of you. So I needed to acknowledge the influence other artists have had on my perception of the world.

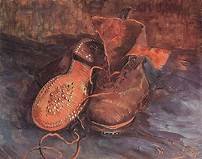

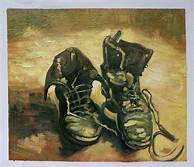

I was inspired to recreate Van Goth’s most iconic still life “Boots” paintings in 3D, and put that inside his most iconic interior, that of his “Bedroom” in 3D, and put that inside his most iconic landscape, The Starry Night, in 3D, like a series of Russian dolls, one within the other. It’s my way of saying all of this extends outwards and is encapsulated in its entirety inside of yet another vessel: Me. And I am in the world, and the world is in the universe, so on and so forth. It’s a homage.

And I’m not done with this. I’m going to make Matisse’s Red Studio, and Pollock’s drip-encased barn, for instance, and on and on.

Can you walk us through the technical creation of The Starry Night Geode?

I see the whole enchilada in my mind’s eye before I begin, so I just follow a pretty detailed inspirational blue print. Occasionally I’ll make a tiny sketch, but that’s mostly to document the occasion of beginning. Making my art is so much easier than, say, putting together IKEA shelves because the instructions seemed to be preembeded, like that recessive gene I mentioned, and all I have to do is let them flow out as directed, or ‘inspired’.

This creative behavior is why I —and most artists—forget that time is passing while they’re at work, why they forget to eat or phone their mothers. Physically, the first thing to do is build the GEODE itself, the rock. I slop a ton of burlap- reenforced plaster over a half-circle mold, creating crevices and bumps and veiny passages just like you’d find on a rock surface.

Here’s a clip showing The Starry Night Geode exterior before painting; Sheesh! —I think that’s Michael Bolton is crooning in the background!

Then I go at that with multiple layers of various kinds of paint and stain, and more plaster splashes, scratches, rough-and-tumble brush work. The exterior of each GEODE is uniquely beautiful but they resemble each other, like precious rocks on a beach; they form a family. I want them to be gorgeous paintings unto themselves. Here’s two different GEODE exteriors…

Making my GEODES is great because they allow me to be two different artists at once: on the outside, I get to be an abstract artist, slopping great gobs of paint around freely and passionately, and on the inside, I get to be a totally anal representational artist, concerned with even the tiniest detail. In the clip below I am being an abstract artist. You’ll see my behavior— my physical action —is similar to that of a bee pollinating, zipping from one spot or flower to next. I don’t have to think about what I’m doing, I just allow it to happen.

Once the outside is dry, I flip the sucker over and begin working on the inside, and each GEODE is depended on the story going in. Here’s a look at The Starry Night Geode flipped over and in progress. I’m about to paint the surrounding foothills seen here in white and you can see the floorboards for his home are in place, but not the walls:

In the case of The Starry Night Geode, I used photos of Van Goth’s works as a reference and generally recreated them as best I could in 3D. Here are a few of his “Boots” paintings that I used as a reference to create my own seen below:

I could shop for chairs, and such, from dollhouse miniature companies and paint them to resemble Van Goth’s. Those elements have to come first because that will determine the scale of the room and the world they will go in. I couldn’t get a bed at the right scale similar to the artist’s, so I just build it myself. If I couldn’t find a hat, or a vase, or a potty that matched the painting, I’d figure out a way to make it. I go shopping for fabrics, doorknobs, and tiny plants… and assemble this enormous inventory of tiny bits that will eventually need to be locked down. Here are some tiny paint boxes, pallets, and paint brushes I made that’ll go on the floor near his easel. Do you think I’m having fun?

The last stage is creating the super-flat, shinny, sparkly rim around the GEODE, to make it look as if the rock had been sliced in half by a big saw, but also to look as though each is circled by a uniquely exquisite aureola. I essentially create a moat into which I pour gems, glass, pebbles, broken mirror, glitter, and tinted resin.

The clip below shows what’s inside a GEODE aureola just before I pour in more resin. I believe that’s The Rice Terrace Geode in progress, which has a green-blue rim. The photo that follows shows The Starry Night Geode’s rim, which is a soft blue.

After that, you hide the thing with all the other GEODES in storage and make another!

Can you talk about the series as a whole?

GEODES serve as a wonderful analogy because they’re a lot like us. On the outside, they're kind of pedestrian, like me, like rocks, you could walk right past one and not even notice it, but on the inside —Woah! Inside you'll find a uniquely beautiful, multi-faceted universe. It's been percolating secretly for millennia, regardless of whether anyone will ever see it or not, like my art. So you have to wonder, why does this inside exist? What's providing its motivation? What force is guiding it and nudging it along? Is it the same force that pushes a flower up the stem? All I know is getting to what's inside geodes —and us— is hard work. You have to bust open that protective exterior. That's the work I've been doing with my art. Ideally to celebrate the inner worlds within all of us. If you’re interested, you can hear a brief story about each of the GEODES so far in the 'WATCH' tab on my website.

Why sculpture and not other mediums such as photography?

Have you experimented with other mediums? My art life actually includes photography and all kinds of other mediums… painting, constructions, installation, film and video, music & sound, as well as writing. I also make a great burger.

My ‘serious’ creative life —beyond infantile mischief—began with music. My brother and sisters and I were all forced to take piano lessons. They all learned to read music, but not me. I just needed to create my own stuff. Our teacher eventually told my mother that lessons should stop for the others but that I had something inside wanting to come out, something he’d never witnessed before. So he continued to teach me, mostly manual dexterity so I was physically able to perform what wanted to emerge. I still cannot read a note of music, but I can hear entire symphony-like things in my head and can recreate them, arranging them for all the instruments, and record them, playing every part, using synthesizers and such.

But I never played for anyone! No, no, no. This was all a big secret that I was both proud and embarrassed about. My teenage girlfriend almost broke up with me because I wouldn’t share what she called my “secret world” and play for her. My mother had to threaten liver for dinner if I didn’t play for her friends. LIVER!

One day when I was 14, some dudes in a music store heard me fooling around on a keyboard and asked me to come with them to their recording studio to jam. I went and they wanted me to just play… do whatever I wanted… and they would join in, while the recording tape ran. The next day, I got a message saying, “listen to CHOM FM at 10 PM.” I tuned in and —holy crap!— I was on the radio! They explained they’d “found this kid” in the music store. Things like that continued to happen to me musically, all of it kind of magical or accidental.

Fine arts, like painting, didn’t really start up until college. I took one art class — “Art 101”— with the clandestine goal of raising my grade point average, and was hooked, seeing it as another veiled language in which I could both document and hide what happening in my life.

Can you talk about your biggest learning experience during the process of creating your art, like your biggest failure?

By far my biggest boo-boos have been trying to explain myself and my art before I was able to do so properly, or before its time, you might say.

In 9th grade, I was desperate to share with my closest friends something that had occurred to me in my room at night. I didn’t want to be the only person in the world shouldering it. So I told them about it. They all reacted with wide-eyed fascination. And they believe me! I was so relieved.

I knew, though, that they wouldn’t be able to fully believe me with my words alone —they needed a first-hand experience, and I needed a way to give it to them, a kind of multi-sensory experience. So I created one. I used my musical and multitrack recording abilities to emulate the sound of what I’d experienced on a cassette tape that I could play for them, to let them experience it themselves. In doing so, in addition to recording wet fingertips on crystal glasses and sucking air through piano strings and other musical effects, I mixed in a borrowed section from an obscure song, the opening drone effect from “I Robot” by The Alan Parson’s Project.

We all sat crossed-legged in the dark in Randi Herlick’s basement around the cassette player, and they listened, amazed, utterly riveted. We all grabbed each other’s hands. We all felt so tiny in the world. We all felt transported into a higher realm. Having my friends experience this was the best thing that had happened to me in the world. But it didn’t last long.

Word spread that I’d heard this extraordinary thing and had taped it. When another close friend, Martin, a music guru, recognized the sound of the song I’d plagiarized, he saw that the whole thing was a shame, a total fake, and told everyone. So my best intentions of sharing my story the best way I could, so people could, believe me, resulted in nobody believing me at all, and utter humiliation. At that time I made a promise to myself: “I won’t tell anyone anything until I can tell everyone everything.” This is partly why I haven’t exhibited my work widely yet.

Despite this lesson, and my promise, I messed big-time up again when I was 23.

Since I wasn’t showing my art, I needed a career to survive and I got one as a creative with a prominent international advertising agency’s office in Toronto. Soon my muse made it clear to me that I had to go off to live in Hong Kong. (That’s another long story.) I ended up being transferred to the agency’s Hong Kong office. There was a bit of hoopla because, at 23, I was by far the youngest person ever to transfer internationally with the company. My boss told me that headquarters in New York wanted a written biographical profile. “A what?!” I asked, terrified. “Just explain how you got here” she explained, “Tell them about your creativity.” Well, of course, I couldn’t do that. I didn’t want to write a profile. I felt totally embarrassed. But my boss forced me to do it, in the third person. “Bryan did this, Bryan did that…”

What came out must have been the most bizarre, fawning, egotistical attempt to explain fortuitous creativity, and how oftentimes you don’t feel you are responsible for it. Meanwhile, the boss’s secretary was to send out a standard PR news release announcing my arrival at the agency, you know, a professional three-sentence appointment notice. Mistakenly, the secretary sent the news release to our New York headquarters and my ridiculous narrative to every newspaper in town. My yucky account of being creative ended up on the front page of the business section of the biggest English language newspaper in Asia, The South China Morning Post. To say that it was an embarrassment is an understatement. The first sentence read, “One thing about Bryan Chadwick is he makes you want to throw up.” Yes, I threw up on the spot.

The agency went into damage control. They asked for a retraction explaining that it was an internal document I had written for our human resources department that was sent out by mistake. That made things worse. The next day, I found my photo emblazoned on the front page and a further lambasting explaining that I had written all this crap myself. They totally crucified me and my professional reputation in the most public way possible. I’d broken the promise I’d made to myself and felt as though I was being conditioned not to do it again.

Everything always turns out great, though. For instance, almost immediately, the South China Morning Post reviewed its advertising account. They invited us to pitch. When I began my creative presentation, I was able to say I needed no introduction with a wink. We won the business and I became their creative director for the next 2-ish years until I was moved to New York.

Don’t worry, throughout all these years doing my “day job”, in Toronto, Hong Kong, New York, Paris, and Amsterdam, I was buzzing away on my art at night, saving for the day I could work full-time on my art while raising a family.

You might be wondering, “Why are you sharing this now? Aren’t you nervous about replying to these questions?”

Of course I am. But I’m also nervous about not participating properly in the art world.

When I had my first public exhibition of paintings, I was 30 and just dipping my toe in, testing the waters so to speak, purposefully as far away from home as I could, where no one I knew would see. I wanted to find out if total strangers could understand what I was saying with my art. An interviewer wanted me to explain my work and, particularly, how I, a Canadian with little to no formal art education, and no exhibits to my credit, could get a solo exhibition at Barcelona’s fabled Els Quatre Gats, the venue of Picasso’s first exhibitions. I couldn’t explain it. I politely declined to say anything. I didn’t cooperate. I told the writer I wanted the art alone to speak for me. He got peeved. As a last resort, he asked for a sketch to accompany his article, so I drew him a kite…stuck in the barbed wire being fried in a high voltage electrical facility. Not a smooth move.

Can you discuss your biggest success since starting your artistic journey?

I wouldn’t call it a success, but an achievement I can be proud of is slogging through the written part of my overall endeavor, which is to create what I call ‘a multi-media codex’, a single work that combines visual art, original music, and a work of literary non-fiction. It is essentially what I’ve been working on my entire life. Just like the recorded tape, I shared with friends to help them understand my world, it will be an attempt to share on multiple levels. My GEODES form just a small part of the visual art component of this project. The whole thing is bonkers because it assumes I’ll be able to get a gallery, a record contract, and a publisher all at once, and get them all to cooperate. Not likely. I think this work is being made for a technological sharing platform that doesn’t fully exist yet.

Although I’d been couching things in art and music, I always knew I’d eventually have to sit down and simply put it in words. And there’s no hiding with words. You just have to say it, beautifully. So, in 1997, I quit my job and ran away to Morocco, the proverbial desert, to spit it all out. I thought it would take a few months. Wrong! It took years, with countless rewrites. In fact, I’m going to go at it again someday, with a new perspective. For my fellow artists, it’s like writing your dreaded ‘artist’s statement’ except giving yourself 400 pages to do so. (Can you imagine anything worse?!) For years, the hidden manuscript has been called A Twenty-First Century Heresy. In my teens, it was titled, This Story Has No Name. But now I’m wondering if I should just call it, An Artist’s Statement. I would love anyone to chime in with feedback. Maybe through your Boynes channel, I could share my other title ideas and do a survey, and get people’s reactions.

What projects are you working on currently? Can you discuss them?

During the COVID lockdowns, my wife Linda and I started an absolutely absurd endeavor. Theaters and galleries were shuttered and trying to connect with audiences on screen, as you know. Meanwhile, as our two boys were being homeschooled on ZOOM, we could see how desperate teachers and theaters were for ‘content’ —arts content especially —that could be easily shared on computers. So we decided to take a page from the French fashion industry who, during the privations of The Second World War, created Thêàtre de la Mode as a way of continuing to show work, using miniature dolls in tiny stage sets. We wanted to do a classic and chose to create a filmed production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, with Linda creating the dolls and costumes (she’s a Tony Award-winning costume designer) and yours truly creating the sets, sound, music, and cinema. And we’re filming our entire process to create “behind-the-curtain” educational content, all of which we hope to distribute fee. Here are a few still frames in which Viola, shipwrecked on Governor’s Island, spies Manhattan Harbor for the first time:

Our production is set in a reimagined colonial New York in which the Native Americans have retained cultural supremacy. (Hence our re-designed Statue of Liberty.) So I built an entire Manhattan and harbor on our dining room table. In fact, the whole production uses only materials we had already around the house. It’s a fairly staggering combination of various creative disciplines. Here’s a link to a “rough cut” of a few sample scenes, if you’d like to see them: Feedback welcome!

https://vimeo.com/611845313

This might seem like a deviation from my core artistic objective, but I’m just trusting that it fits in somehow… this is going to teach me about something else I need to do or perhaps how to recount my own story. Many artists have ventured into theater… Chagall, Matisse, Picasso, and Hockney to name a few, and museums delight in showing their efforts. Alexander Calder’s “Circus” at The Whitney Museum comes to mind. We hope to display the dolls and sets in a gallery setting one day, along with a screening of the play. Each set element is an artwork unto itself. Below, for instance, is a doorway I created for one of the Native American households:

Besides Twelfth Night, I’ve always got multiple things on the go. I’ve got four new SUGAR STICKS in the works. These totems are about how I used to ‘sugar coat’ my stories, make them funny or charming, so they’d be more acceptable and less embarrassing. Below is a small blue one newly installed in a collector’s garden. The next set, all in different colors, are significantly larger, including a truly monumental yellow one. Each of them takes about three months to make.

I’ve got a new GEODE cooking! “The Cascade Geode.” I’d love to tell you about that and share work-in-progress images and films if you’re curious.

I’m completing all whole series of my SKIES, which are about how the turbulence we see in the sky is similar to what goes on in your head when you’re being overtaken by creativity. Here are two that I just unpacked from the framers today:

I’ve also been at work on a series called “STRAYS” in which I photograph the impacts left behind by stray bullets from real shootings and senseless violence in and around New York. They seem to show how one tiny thing can radiate outwards to affect what appears to be the entire universe. That’s kind of like what I experience or perceive in my creative world. Here are two examples:

I’m excited to be informally invited to share ideas and proposals for large-scale murals and installations at New York’s Brookfield Place and its Winter Garden… Can you imagine thirty GEODES scattered around there?! It’s totally speculative at this point, and long shot, but here’s a peek at the type of painting work I’m putting forward. This is a mock up:

At all times I’m advancing all the different projects you see listed on my website; everything I do is ‘ongoing’, which is why I don’t share work by ‘year’ like most artists but rather by ‘series’.

What advice would you give to your fellow artists?

Gosh, I don’t feel like I’m qualified to give advice! But, if you’ll indulge me… I’d ask them to remember that creativity seems to come ‘through’ you. It comes ‘out of you’. Don’t you agree? What then is the exact content, meaning, message, and source of what is going in?

To view more of Bryan Chadwick’s work: