Artist Flora Ranis

Congratulations to Flora Ranis for earning her place as a Finalist in the Boynes Artist Award 9th Edition [Young Artist category]!

Who are you?

My name is Flora Ranis, and I am an artist. I was born and raised in the Florida Everglades, where marsh and moonlight dance under warm, sticky sun. In high school, I enrolled in various art classes, and when the COVID-19 pandemic closed schools during my senior year, I found peace in painting. Forbidden from visiting friends and from even exiting the house at the height of the pandemic, I woke up every morning excited to blend brush and paper, to practice the divine act of creation, and to document an uncertain and ever-shifting world. For many years, I declared art a hobby, banishing the creative act to collect dust in the corners of my life. I often devalued my own work and existence, unable to celebrate that which is not widely respected. However, as I entered college and engaged more and more with activist organizations dedicated to abolition and decolonization, I discovered great power in painting, in not only creating political art but also creating as a political act, one that pushes viewers to perceive the irrationality of a trans-apocalyptic world and to, above all, feel. As a young woman, it is easy to feel overwhelmed by a world working tirelessly to decrease your bodily autonomy and personhood. However, through art, I continue to fight, to question systems of knowledge and understanding, and to explore what it means to be alive in the 21st century.

“Clean”

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

What inspired you to utilize Painting as a medium?

I have often wondered why my body gravitated toward paint rather than charcoal or clay or, frankly, any other medium. I often experiment with different materials, and yet I find myself constantly returning to paint, and watercolor specifically. When I first used watercolors my senior year of high school, I could not believe how quickly and seamlessly new hues appeared, how they danced with one another, swirling their bodies in harmony and rejection, and how they bled so softly and so vibrantly into the paper’s coarse fibers. I fell in love with the unembellished nature of watercolor paints, which require nothing more than water and can be breathed in and touched to the skin. Due to the fluidity of water, one is simultaneously encouraged to create intricate details while forced to relinquish control to the very substance required to sustain human life. In a way, with watercolor, one is always painting themself, a portrait and proof of life.

“Quench”

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

How would you describe your ARTwork?

My work reflects the irrationality of the world within which it was created, one that publicizes celebrity sightings beside death tolls, one that codes the most violent species as the most civilized, and one that jumps in the pool even as the waters rise. My works are rejections of systems of oppression that promote stagnation and desensitization. They are celebrations of the body, of menstruation, of blood and bone in celebration of the fiber and fat often regulated and deemed inhuman by modern legislation. I saturate faceless, colored canvases to reflect the hypocrisy of purported human civility and juxtapose unvarnished images with vivid pigments. My works honor the body while urging viewers to question what it means to be human and alive. I paint blood, bone, and tissue not because it is what I am made of but because it is who I am.

“Bloody”

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

Can you discuss the inspiration and thought process behind your winning work?

As a Jewish woman, I am fascinated by religion, the beauty and war generated through community, and the traditions warped by modernity. Rather than following a specific text or believing in a specific deity, I find faith in community, in singing arm in arm, in sharing worries and wisdom with those willing to listen. When growing up, I cherished the empty corners of the Torah, which had been touched and flipped by hundreds of human hands but which contained no teachings, no rules, and no tenets to guide them. To examine my own modern fulfillment of ancient texts, I turned to painting. I wished to explore the hypocrisy of both my personal practices as well as prescribed teachings through the juxtaposition of objects containing holy and cultural significance with violent and unorthodox materials. I created a series of paintings, one of which features shot glasses filled with the kosher wine Manischewitz and adorned with slices of lime. A separate painting features a ripe pomegranate bleeding open, its seeds splattered against a pristine Seder plate. In the painting Sabbath, which features a cooked ham wrapped in a tallit, I investigated the Judaic intersection of slaughter and sterilization. Like American slaughterhouses, biblical texts transform murder into ritual, branding certain killings as requisite and others as blasphemous. By wrapping the forbidden flesh and meat of a pig in a tallit (a sanctified garment that allows Jews to become closer to God during prayer), the painting Sabbath challenges the purported holiness and purity of the human species, one that delineates certain beings as too unclean for death and devouring. Additionally, the blood of the ham mirrors menstrual blood, a substance similarly coded as indecent and unholy throughout religious texts. What does it mean to wrap blood and body in holy tissue, to make oneself sacred?

“Sabath”

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

Can you walk us through the technical steps of creating your winning work?

I usually paint the most intricate portion of the painting first, so I began with the flesh of the ham.

I then worked closer and closer to the painting’s edges, expanding beyond the flesh of the ham to include the fabric of an embroidered tallit and the metallic sheen of two Shabbat candle holders.

I painted metal cups on the right side of the painting to add balance to the composition. I mixed burnt orange and deep blue to create a more complex, bright gray.

I finally painted the background a subtle blue to connect the embroidered portions of the tallit to one another and engender greater balance and unity within the work. I also added small splatters near the bottom edge of the painting to contrast the stagnant nature of the sitting ham with the fluid violence of dripping blood.

What do you hope to communicate to an audience with your work?

My greatest hope is that viewers feel something upon seeing my work. My painting describes a scene that has never occurred, one that is considered blasphemous and sacrilegious and somewhat comical. I did not create the painting to advocate for or against the consumption of meat deemed unclean but rather question how such delineations arise. What does it mean to be unclean? What does it mean to make oneself clean? What does clean consumption look like? I hope viewers examine the rituals and routines that govern their lives as well as their own understandings of good and evil, of holy and tainted. If any viewer feels uncomfortable, I hope they sit with such discomfort and pause to reflect where such disgust and fear stem from.

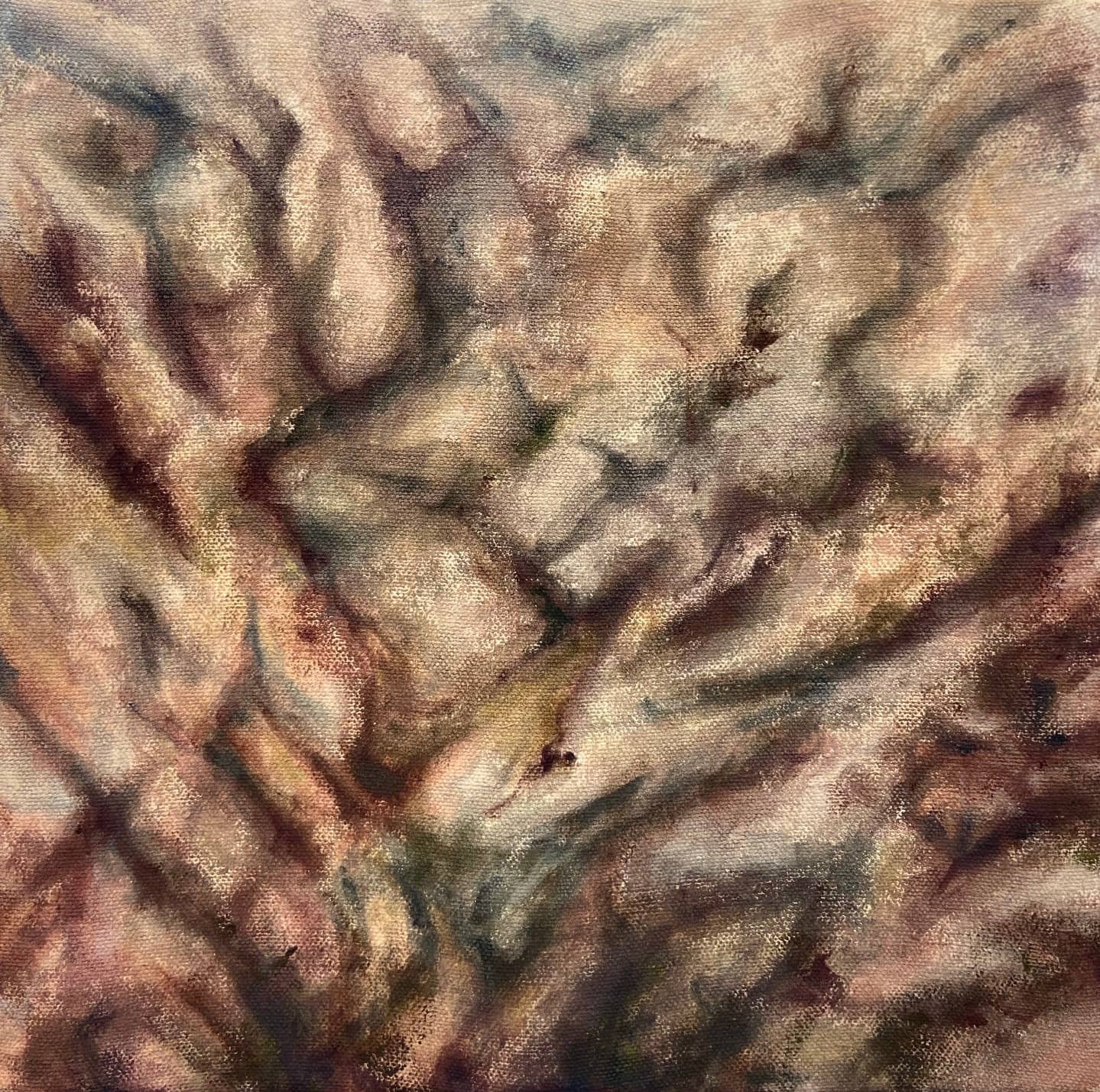

“Menstruosity”

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

Can you talk about your biggest learning experience during the process of creating your work?

While learning to paint with watercolors, I had often been told to use plenty of water and blend extremely well. Such practices helped prevent me from tearing through the paper and increased the accuracy of my hues. However, while completing this painting, I learned an unorthodox technique that allowed me to treat watercolors as dry pigment and better depict the texture of meat and flesh. I began to use less and less water as I darkened the ham and added shadows between ligaments and tendons. Using a dry brush allowed me to generate tiny, coarse, broken lines that mirrored the fat of the original ham. I was soon utilizing such little water that I worried the paper would weaken and shed, but such slight tearing added to the texture of the meat, allowing me to create dry, rough segments of ham that appear slightly burnt and unnatural. Though using a dry brush with watercolors is often denounced, the resulting rough paint may highlight the blended, soft aspects of the painting and generate an engaging contrast between coarse details and smooth swaths. Though there are approved manners of working with every painting medium, it can be freeing to generate your own methods and learn as you experiment.

“Vulgar”

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

Can you discuss your biggest success since starting your artistic journey?

I believe my biggest success would have to be a very simple realization: that I wish to dedicate my life to the creation and celebration of art. Art guarantees little financial security and stability, and for many years, I was afraid of calling myself an artist and failing. I worried about burnout and losing my faith, of forgetting why I began creating, and being unable to support myself. However, over time, my commitment to creating and my passion for this work allowed me to quiet my fears. I find myself falling asleep excited by future projects and new ideas and novel ways of interpreting and interacting with our world. Even when I am stressed and anxious, art grounds me and allows me to express myself. Though deciding to pursue art may seem straightforward, it required many long nights, sore backs, and uncertainty. But it was only after experiencing discomfort and rejection that I realized just how much art means to me and how much I’m willing to fight for it. In the future, my greatest success may look very different, but for now, I am grateful to apply, to try, to take the risk.

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

Can you share with us the best piece of advice you you wish you had known at the start of your career?

During my junior year of college, I expressed to a professor my fears regarding burnout. As a student artist with coursework, multiple jobs, and a small case of insomnia, I worried that I would wake up one day exhausted and disinterested in art, that I would grow tired of painting and lose my passion for creating. I asked him if he ever felt similarly, if he too ever felt overwhelmed and anxious by his profession, and he smiled slightly. “How do you define art? How do you define creation?” he asked me. “When I make my bed in the morning and make a cup of tea at night, I am creating,” he said. He continued, explaining that art cannot not be shackled to a piece of paper or wall, that it is something lived and experienced rather than produced. Artists should honor the hours spent resting, eating, laughing, and imagining just as much as the hours spent sculpting and painting, for 99% of creation occurs outside of the studio. In essence, to dream and live is to create. Waking up is already an act of creation.

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

What projects are you working on currently? Can you discuss them?

I am currently working on a series of paintings honoring queer individuals from my home state of Florida. In 2022, Governor Ron DeSantis signed what opponents termed the “Don’t Say Gay” bill into law. The legislation banned classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity, deeming queerness inappropriate, impermanent, and unnatural and otherizing and erasing queer Floridian youth. This project counters such legislation by depicting queerness as natural, powerful, beautiful, and enduring. The paintings will weave transgender, genderqueer, and gay individuals into mangroves, marsh, and moonlight, connecting the vast beauty and power of queer bodies with the vastness of Florida’s river of grass.

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

What is your dream project or piece you hope to accomplish?

A: It feels as though every week my dream project changes. As a young artist, I have enjoyed exploring various mediums and subject matters and hope to push my practice even further. I have fallen in love with painting over the years and hope to expand my practice to include metalworking and sculpture in the near future. Through painting, I have explored what it means to be human and alive in the 21st century, and I plan to examine similar themes through works that command an entire room and cannot be hung on a wall. By sculpting disturbing, life-size human bodies, I hope to expose the hypocrisy of war, the corruption of corporations relying on fossil fuels, and the irrationality of a trans-apocalyptic world.

Watercolour on paper

By Flora Ranis

Lastly, I like to ask everyone what advice they would give to their fellow artists, what is your advice?

Call yourself an artist, proudly, regardless of how many works you have created, how many you have sold, and how much money you have made because to be an artist refers not to a profession but a perspective. To be an artist is to view the irrationality, hypocrisy, and beauty of the world without shying away. To be an artist is to feel the world fully, to move your limbs and muscles and mind and breathe life into paper and product, to make oneself human again and again and again. So, please, do not give up when your work does not appear as you had envisioned or when rejection letters flood your inbox. There is no company nor critique that can change who you are. You have the incredible ability to dream and reimagine the world, and I hope you never forget it.

And if you are searching for community or would just like to chat and connect with another artist navigating this world, please reach out! My email is flora.ranis@yale.edu. Looking forward to hearing from you!

To view more of Flora Ranis