Artist Huner Emin

Congratulations to Huner Emin for earning his place as a Winner in the Boynes Monthly Art Award December 2022!

Who are you?

I am a stateless Kurdish artist. I grew up in south Kurdistan/northern Iraq and am now based in Bloomington, Indiana. I studied Western classical art in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah, Iraq and moved to the United States to earn an MFA in Studio Art, Painting at Marywood University.

From childhood, I was influenced by my uncle, an amateur artist and poet. He used to draw motif artworks and surreal representational narrative-based works on the walls of my grandfather’s house in the village. In my teenage years, my interest in visual arts was replaced by poetry. Later, I was accepted to the University of Sulaymaniyah College of Art, which is when I jokingly say I had an arranged marriage with art, because I was interested in studying journalism as it was close to my then-hobby of writing. Studying art in the university returned me to my childhood passion for visual art, but I also took a serious dive into theory of art, philosophy, and aesthetics despite the lack of art resources in Arabic or Kurdish in Iraq.

It was my interest in journalism and curiosity for truth that led me to investigate creating time-based performance and installation art since my early artistic career. I was most influenced by Western styles of art making while I was living in Iraq. I admired performance art and conceptual art, and my political interests influenced the creation of artwork that are political. Later on I began to call my artistic practice Investigative Art, which is a term I coined to describe my work and combines the two fields of I’ve always been interested in: journalism and art.

In 2013, I created and implemented an outreach art program called Art for Dumiz’s Camp in the Kurdistan region of northern Iraq. It was a collective project that worked to integrate child refugees from Syria into their new society and support them in processing and expressing their living situation through art and creativity. In this project, I organized and supported artists to conduct art activities inside the refugee camp, such as creating art, teaching art, and music concerts.

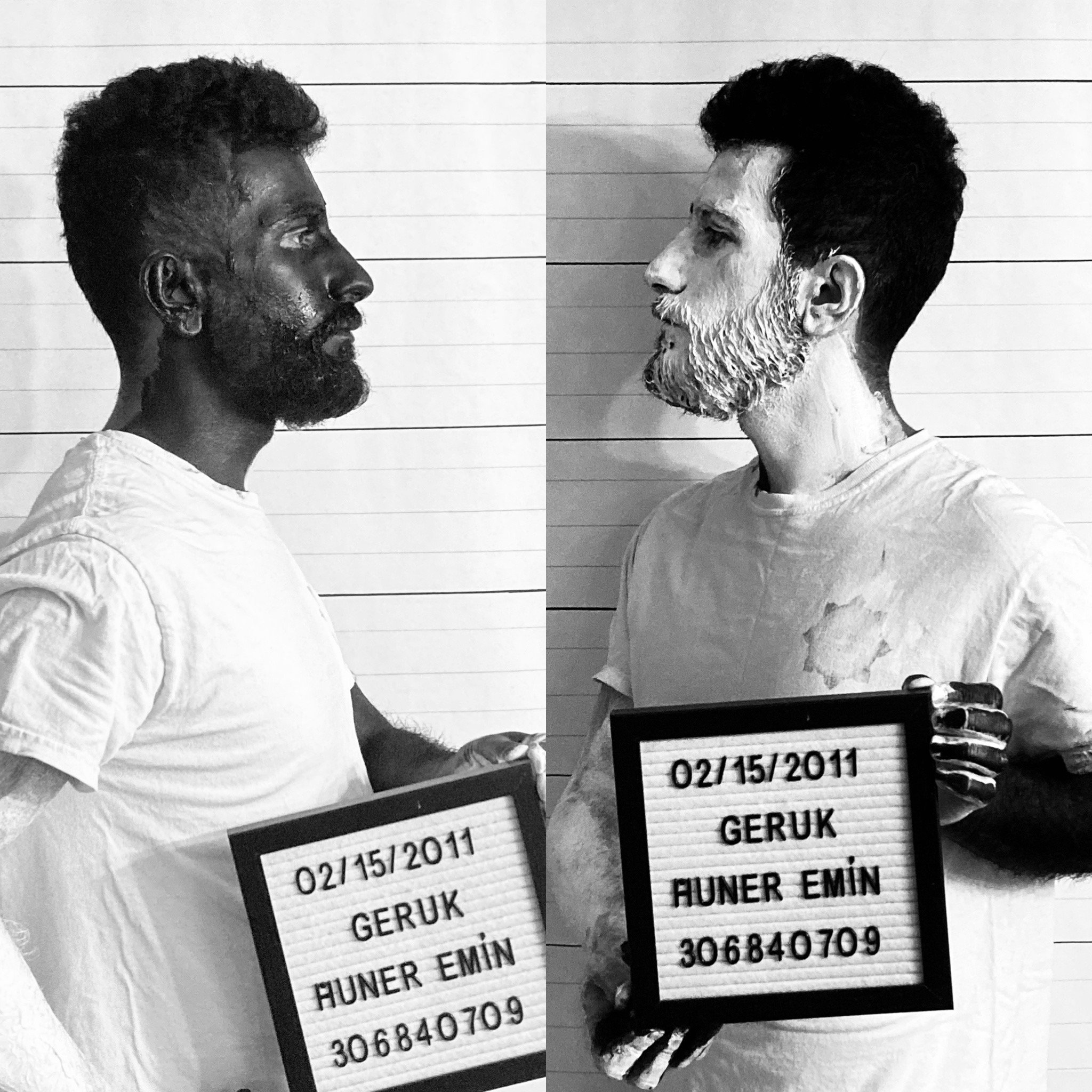

Since leaving Iraq in 2013, I have never returned due to political and social issues. During the Arab Spring, I performed an art piece called Geruk, questioning Iraq's power and political dogma. This performance led to my arrest twice between 2011-2013 by authorities in northern Iraq. Between those two years, I was also living in fear of the honor killing tradition. After five years of juvenile and puppy love with my neighbor, her brother found us. Due to the practice of honor killing, my family had to leave the village where we used to live. I was worried that I would get stabbed by my former neighbor’s brother in response to my romantic relationship with a member of his family. In 2017 I created an artwork that addresses the honor killing tradition, and this event of my life, called Blood Washing, first exhibited at Maslow Study Gallery for Contemporary Art at Marywood University.

During my MFA study, I performed an artwork in Kresge Gallery at Marywood University called 180,000 Seconds in memory of Kurdish victims of a genocide campaign conducted by the Baath regime between 1987 and 1989. The number 180,000 represents the number of victims, which is the time I spent standing on my feet performing this art piece for fifty hours over five days. The first two years of my life were during this military operation called the Anfal Campaign.

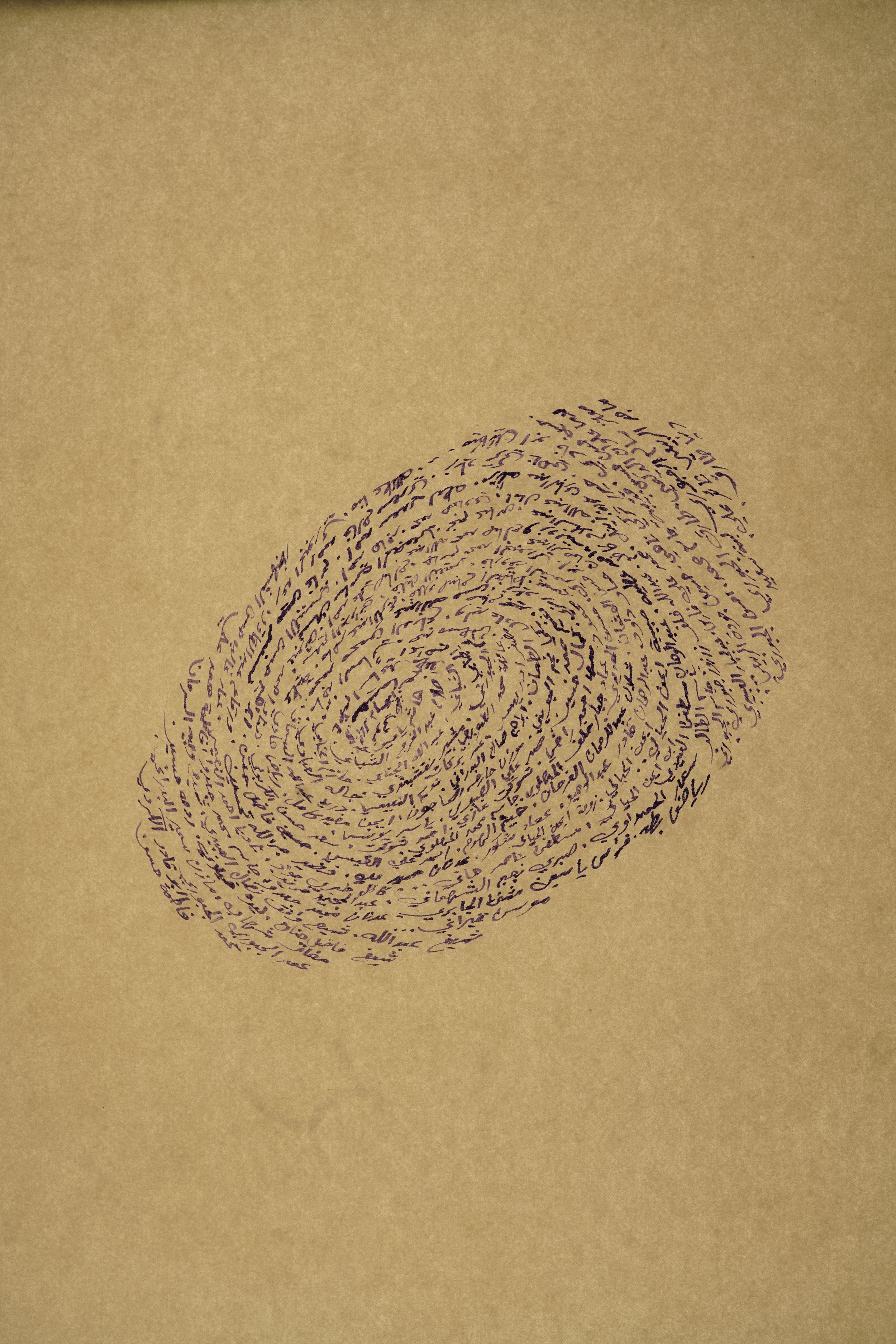

Since 2021, in the wake of the hoax of the American Dream, I have been collecting the names of Iraqi civilian victims of wars from 2003-2017 and handwriting the names in the shape of fingerprints, with purple ink on paper, to reflect on the crimes against humanity in Iraq. Inspired by the book Manufacturing Consent by Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky, I named my artwork Manufactured Democracy and revisited images of the first Iraqi election after the invasion of 2003, called the Purple Fingers Election because of the purple ink indicating that people had voted.

“180,000 Seconds”

Performance Installation

By Huner Emin

What inspired you to utilize mixed media as a medium?

Of course, at an early age in studying art, every artist gets influenced by a movement of art or a mentor. For me, it was my highly talented and intelligent professor Namo Rustamzada at my bachelor’s degree in Iraq. Namo was and still is inspirational to my artistic career. We would sit in his experimental painting class, and he would translate Omar Khayam’s poems from Farsi to Kurdish for us. He had such an idealistic view about art, the Kurdish political situation, and literature that made a visceral impact on my art process. He encouraged us to feel for the objects we were making rather than copying a subject, almost like making art with our hearts rather than our minds. Despite having incredible classical art painting and drawing skills, Professor Namo introduced performance art, installation, and conceptual art to us as well.

I was inspired by Namo’s ability to think like a Renaissance master as he worked on many areas of creativity including art, science, and language. He resurrected an ancient and extinct Pahlavi calligraphy and wanted to implement its use in the Kurdish language, instead of using Arabic or Latin alphabets, an ambitious attempt to unify the Kurdish languages and writing. In my later painting career in the United States, I began borrowing Namo’s resurrected writing style for use in my artworks.

From my early art career, my artwork has been multimedia, performance art, and conceptual. Namo’s influence opened my eyes to art’s route in the western world. When I was in Kurdistan, I looked to the west for the style of art I wanted to make. I was overwhelmed by the abstract expression movement and was doing performance art. In my opinion, up until then, I was imitating western art. I didn’t see authenticity in my practice, even though my performance art tended to be more original.

After getting my MFA in the United States, I familiarized myself with the art scene, and I returned to my origins, understanding the weight of eastern culture. I began creating artworks that contained videos, as well as installations with light boxes and calligraphy. Somehow, the new and investigative art pieces represent the eastern and western worlds. In my mind, the videos represent the eastern oral culture. Meanwhile, the installations represent the western predominantly materialistic visual culture. It is a bridge I wanted to stretch between two cultures to reflect on my struggle, being transplanted in exile. My art process explains my interest in journalism and investigative works.

“Geruk”

Multimedia

By Huner Emin

How would you describe your work?

My work is multi-disciplinary, and I call it investigative artwork. I use juxtaposed medias of video and installation or sometimes calligraphy and lightboxes. Usually, my artwork is time-based that has a direct link to my life and personal story. I think to keep it authentic and genuine by keeping my subject matters related to my life. Since I work on heavy political subjects, such as genocides, suppression and honor killing I find it more believable to relate the artworks to my personal life.

“Blood Washing”

Multimedia

By Huner Emin

Can you discuss the inspiration and thought process behind "Manufactured Democracy"?

The idea of Manufactured Democracy came to me right before the Covid-19 pandemic. I was living and working as an art handler in the District of Columbia. As it was required for my art handling position to drive trucks long distances, I traveled across the United States on highways and was paid barely enough to survive. On these travels, I was being introduced to American culture while listening to audiobooks. The idea of the United States to me was deteriorating, and the hoax of the American Dream appeared to me when I listened to Manufacturing Consent by Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky. I observed the massive gap in the quality of living between people who collect art and the ordinary working class. I also saw a fragile society on the brink collapse with people living paycheck to paycheck in swamps of poverty and massive income inequality in the US. I saw the leaders and beneficiaries of the system glorifying the American empire. Meanwhile, I was overworked and underpaid and saw many other people like me living in poverty.

I thought about my country of origin and how Uncle Sam’s giant propaganda machines sold misleading ideas of freedom and prosperity to Iraqis. Back in 2003, at the beginning of the American invasion of Iraq, when war was broadcasted on TV across the world, I remembered seeing footage of an American soldier standing on a tank, speaking to the camera and saying, “how could this country [Iraq] be the cradle of civilizations when I don’t see a Burger King or a McDonald?” For some reason, I still remember that interview. I asked myself, is this the democracy and freedom the United States wanted to export to my country? Is this the freedom of speech and well of choice that the US tanks wanted to establish in Iraq--to be able to eat in a fast-food chain restaurant? How could I have believed the lies in my teenage years?

I realized that I was a victim of the US propaganda and believed that Iraq would thrive after getting liberated from its brutal dictator. Images of the first Iraqi election after the invasion came to my mind when my fellow citizens showed their purple index fingers to cameras. Each individual who voted in that election was asked to dip their index finger into a cup filled with ink to indicate their participation in the Iraqi democratic process. That election was later called the Purple Fingers Election. I had just turned eighteen and dipped my finger in the ink.

The Purple Fingers Election was a symbolic gesture and a false narrative that Iraq would finally be free from its brutal and deadly regime. The last twenty years of Iraq’s modern history have been overwhelmed with violence, civil wars, and political instability. The estimated number of Iraqi victims of civil wars exceeds a million. Along with massive migration waves, family displacement, massive waste of Iraqi wealth, and the ruin of its infrastructure, these conditions are the result of US foreign policies and its interference in Iraq’s modern history.

It was a healing and meditation ritual to think about writing the names of Iraqi individuals who lost their lives after the second invasion of Iraq by the United States-led coalition army. I looked for a list of names and body counts online and contacted the Iraqi government and institutions, but I couldn’t find any. Finally, I found a nonprofit organization online called Iraqi Body Count, which sent me an Excel sheet that has 13,000 names, many of them just a description of the body count rather than the name of the victim.

So, I thought that the Iraqi victims appeared to be insignificant and an abstract number to the international community and the giant media machines of the United States. It appeared that even the Iraqi government doesn’t record the victims of wars properly as well.

I wanted to create an artwork that depicts the scale of crimes against humanity in Iraq. Writing the victims’ names in the fingerprint shape suggests a crime scene, and the fingerprints reflect on my memory of the Purple Fingers Election.

“Manufactured Democracy”

Ink on Paper

By Huner Emin

Can you walk us through the technical steps of creating "Manufactured Democracy"?

After receiving the names of Iraqi victims, I thought to write the names in the shape of fingerprints to depict a crime scene. At first, I wanted to borrow the fingerprint biometrics of politicians who were directly involved in orchestrating the second Iraq war, such as George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, and Donald Rumsfeld. Ideally, it would have been meaningful to use the fingerprint of each Senator who voted for the second Iraq War. Soon, I realized that it was impossible to obtain these individuals' fingerprints. So, I just used generic fingerprint shapes sourced from the internet.

From the beginning, I wanted my artwork to be placed on light boxes to highlight the victims’ names. I wanted to write the names close to each other so that it would be harder to read and that the audience would need to get very close to decipher them. I also wanted to write the names in purple ink and to write them in Arabic calligraphy, as it is the dominant writing style that is being used in Iraq. It would have been disingenuous to use computers and technological tools in writing and designing the fingerprint.

The list that I received was in the Latin alphabet, and translating the names into Arabic added another layer of repatriation to their original language.

“Manufactured Democracy (Detail)”

Ink on Paper

By Huner Emin

What do you hope to communicate to an audience with your work?

I want to use art as a tool to document the atrocities and devastation that we, as human beings, are bringing to this world. The time for the contemplative and imaginary rule of art has passed for me. We live in a world filled with miseries, atrocities, and suppression, and in the process, we are destroying our planet. I believe art is a tool to point at oppressors and organize ourselves. Art has been distanced from the public. Ordinary people feel left out of how to read or understand modern art. I want my art to be serious, easily read, and understandable.

“Manufactured Democracy 1”

Ink on Paper

By Huner Emin

Can you tell something you wish you had known before or when you began your career that would have really helped?

I wished I was fluent in English in my early art career. It seems that it is imperative for artists to speak English to reach wider audiences and to take advantage of the opportunities that are available for English speakers. Perhaps that is a serious issue that needs to be discussed in art discourses because I believe there are many artists in the Middle East who deserve recognition internationally and are limited in resources just because of language barriers. An example would be my professor Namo.

“Manufactured Democracy 2”

Ink on Paper

By Huner Emin

Can you talk about your biggest learning experience during the process of creating your work?

I relearned how to write in Arabic calligraphy in the process of making Manufactured Democracy. In the last ten years, I learned and practiced English significantly more than other languages, and when speaking Kurdish, I used Latin letters because it suits better with Kurdish sounds. Arabic calligraphy as art itself is complicated and requires years of training.

I also learned the ancient and extinct Persian empire writing style that was resurrected and modified by my professor Namo Rostemzade.

“Manufactured Democracy 4”

Ink on Paper

By Huner Emin

Can you discuss your biggest success since starting your artistic journey?

The biggest success of my artistic journey was creating an art program that helped Syrian refugees to integrate into the Kurdish society in northern Iraq. I organized and collected more than 30 artists to teach art and music in a Syrian refugee camp in Duhok. Our objective was to reduce the stigma around refugees and to welcome them into their new place. Even though most refugees spoke the same language as the locals, they were still facing hostility. Our project, called Art for Domiz’s Camp, was to create a bridge between these communities, both locals and newcomers.

“Blood Washing (Detail 1)”

Multimedia

By Huner Emin

What projects are you working on currently?

I am working on two projects. The first one is related to school shootings in the US. Around the time of the Uvalde school shooting, my wife and I found out that we were having a baby. I began recording the sound of our baby’s heartbeat to use it synchronized with the sound of gunshots and the number of school shooting victims.

The second project is a long-lasting art project that is related to Yezidi victims of the ISIL wars in Iraq. Yezidi is a minority group in northern Iraq that faced genocide and ethnic cleansing under ISIL’s control in northern Iraq. I have collected the stories of the victims. I am in the process of turning them into short film scripts that will eventually be turned into an art installation inspired by the victim’s experience of ISIL captivity. I imagine making light boxes with the script illuminated and written in the calligraphy that Namo has resurrected. Currently, I am looking for a residency at a university or a museum to complete this work. I am also looking for support from the Iraqi government, art institutions, and human rights organizations to finish this project, and I am still waiting to receive any help.

Click this link for the two examples of the scripts

“Blood Washing (Detail 18)”

Multimedia

By Huner Emin

What is your dream project or piece you hope to accomplish?

My dream project is about Yezidi victims of ISIL wars in Iraq. It is a project that requires a lot of time and attention to detail, as well as multidisciplinary art making.

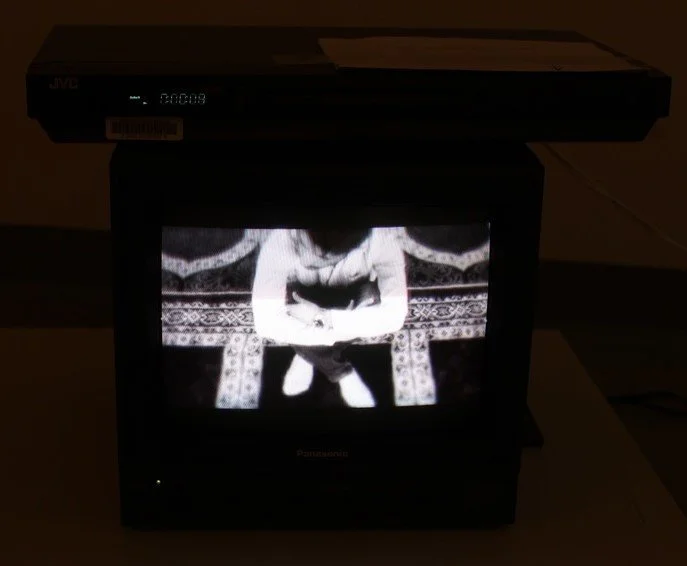

“Blood Washing (Video)”

Multimedia

By Huner Emin

As a winner, do you have any advice for artists who want to submit to awards, competitions, residencies, etc.?

Don’t be afraid of getting heartbroken or turned down so many times. (Maybe this advice is also for me).

“Submission”

Multimedia

By Huner Emin

Lastly, I like to ask everyone what advice they would give to their fellow artists/photographers, what is your advice?

I advise artists to be genuine and authentic with themselves and express their truth. Don’t settle for what is easy and acceptable. Work hard, be ready, and take advantage of every opportunity in front of you.

To view more of Huner Emin’s work